As oat based cosmetics continue to hit the shelves CHMSN member Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan looks at one of their historical predecessors.

“Just five short minutes every day –

Five minutes in the OATINE way.

A little time; a pleasant duty

And all may win complexion beauty”

In 1905, a new beauty product emerged on the British market. Advertised as “the food for the complexion,” Oatine – as the name suggests – was an oat-based face cream that aimed to “bring natural beauty to the plainest face.” The cream was widely promoted across the national press through competitions and free samples, with the ‘Oatine Girl’ becoming the face of the campaign.

The product was an instant success and, soon, the Oatine Company was producing manuals on beauty and personal hygiene for women, such as Beauty and Health: How to Attain and Preserve Them (1913) and The Oatine Book: Oatine Aids to the Preservation of a Beautiful Complexion (1920). Gradually, the Oatine range expanded to incorporate face powder, soap, shampoo powder, toothpaste, snow (i.e., vanishing cream) and even a “magician beauty roller,” which women were encouraged to run over their skin after applying Oatine to get rid of wrinkles, double chins and sallow skin!

During World War One, Oatine capitalised on the shocking stories of the ‘Canary Girls’ – women working in munition factories whose skin had turned yellow from exposure to TNT. Advertisements claimed that Oatine could protect the skin from TNT damage by removing “dust and grime” from the pores. No scientific evidence was ever put forward to support this bold claim, but many anxious women were duped into the belief that “prevention is better than cure,” as the Oatine advertisements repeatedly reminded them.

By the late 1910s, the Oatine Company had expanded its business to France and, in 1922, to Scandinavia, now boasting headquarters in London, Paris, Malmö and Copenhagen (and, later, Oslo and Stockholm). Sweden in particular represented a new and exciting market for the brand as women had recently obtained the right to vote and were entering the workforce in greater numbers. Fashion and beauty products became viewed as essential accoutrements to this ‘modern’ lifestyle.

Swedish Oatine advertisements targeted this new audience with images of glamorous women with marcel style waves, heavily made-up eyes and clad in dresses, furs and boas. Often, the women held up a mirror to their faces, hinting at intimacy and sexuality, but also emphasising that it was possible for ‘everyday’ women to recreate this level of beauty in the comfort of their own home (see Runefelt, 2019 for an excellent paper on this). Emotive headlines accompanied the images, declaring that “Beauty and freshness should characterise the typical Nordic woman.” The only way to live up to this standard was, of course, by using Oatine daily. Other advertisements made assumptions that women’s greatest concern was their appearance. “It means so much to you that your face looks pretty,” they rather patronisingly asserted.

The transformative effect that Oatine supposedly had on the skin is apparent in a 1929 advertisement entitled “Who is she?” and featuring a sophisticated woman in a white boa and headscarf. The ad copy states:

Who is she who enters the room – in a white boa – and with a beautiful complexion? She looks so self-assured because she knows that she is sacrificing the necessary time to preserve her fair, beautiful complexion… she uses Oatine morning and night like millions of others who have learnt to appreciate the wonderful properties of this cream.

Here, being prepared to “sacrifice” one’s time for beauty is seen as “necessary.” In other words, women must adhere to a clear set of beauty standards by disciplining and reshaping their complexions (cf. O’Hagan, 2022). Not to do so is to go against their feminine nature. However, at the same time, women’s ‘trick’ to achieving this must be kept secret – what Wolf (1990) terms the “mystique of feminine ideal.” Oatine, therefore, could help women realise their own beauty potential, yet they must remain as natural looking as possible so as not to compromise their female identity.

Oatine was not only the right choice for smart and modern women to remain beautiful, but it was also empowering because it could offer women broader sociocultural aspirations, such as finding and keeping a boyfriend. A 1928 advertisement shows a man picking up a woman for a date. As he helps her into her coat, he exclaims, “You’re always so soft!” The woman replies, “Yes, I follow the golden rule – looking after my skin with Oatine.” The advertisement goes on to claim that this is the “secret” to keep men happy.

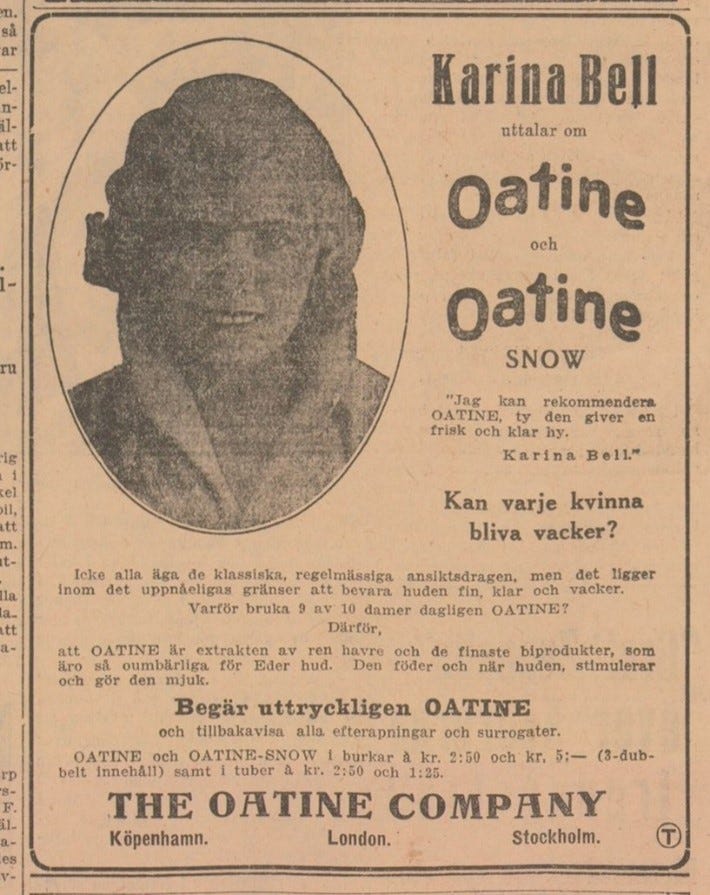

Advertisements also frequently used celebrity endorsements to show that every woman could become more like these role models if they purchased Oatine (cf. Schweitzer, 2004). The famous Danish actress, Karina Bell, openly claimed that Oatine guaranteed “fresh and clear skin” to which the Oatine advertisement asks, “Can every woman become just as beautiful?” Its candid response: “Not everyone has the classic, regular facial features [of Bell], but it is within the limits of what can be achieved [with Oatine] to keep the skin nice, clear and beautiful.”

However, advertisements were also just as likely to feature everyday Swedish women as authority figures in an attempt to make a personal connection with consumers. A case in point is a 1928 advertisement, which shows two stylish women chatting over lunch. Their conversation is captured in italics underneath the image:

Dear Maja!

The other day, I went to Tora’s house. You would have screamed if you’d seen her. I thought she’d had an accident. All her skin was covered in bandages, she looked in pain and swollen and was given boiling hot wraps every now and then, so as to be treated afterwards with several types of creams.

I couldn’t help but scream as I sat down, and do you know what she said? That with my COMPLEXION, I really had reason to smile. “Dearest Tora,” I replied, “Just do as I do and use Oatine. It’s a pure oat extract. I use nothing else. You see the results right before you – you won’t find a better beauty remedy.

The conversational and informal style of speech sounds authentic and was likely to resonate with female readers. The accompanying copy offers a more professional take on why “most women prefer Oatine”: “it stimulates, purifies the blood, is refreshing and keeps the skin clear and soft.”

This matter-of-fact attitude on the benefits of Oatine can be seen across the advertisements with claims that “everybody believes that you look younger if you use Oatine daily,” “all experienced ladies with knowledge about face care use Oatine daily” and “everyone desires fine, soft and clear skin.” This sets up a dichotomy between responsible and irresponsible women, implying that those who do not buy Oatine or take the time to learn about its benefits do not care about their appearance and are, therefore, bad people.

To this end, scaremongering is also often used in advertisements, with women warned that their faces “age prematurely due to improper treatment” and the only way to maintain “an enchanting face” is through “daily treatment” with Oatine. The idea of Oatine as a ‘treatment’ plays into medical discourse, putting the product forward as a “unique” remedy to “protect” the skin, maintain its elasticity and “free” it from premature aging. Taking this medical discourse further, other advertisements even describe Oatine as an “antiseptic” that prevents infections.

Other advertisements instead play up the natural side of Oatine. While seemingly contradictory to mention nature and science together, Santos (2020) notes that this approach in beauty marketing was not as paradoxical as it might seem because beauty was originally a kitchen physic, where preparations were made at home using plants, flowers and herbs. As products became taken out of the domestic context, beauty companies exploited this tradition in their marketing to invoke feelings of homeliness and safety, yet also added supporting scientific evidence to modernise and validate these traditions.

This emphasis on nature is seen most clearly in a 1929 advertisement entitled “I Am the Oat,” where the Oatine cream is personified and given its own voice: “I am the oat. Oats are my origin. Since ancient times, I have been appreciated for my ability to beautify the skin. To build credibility, the text is accompanied by an evocative image of a traditional female peasant holding an oat sheaf in one hand and a jar of Oatine in the other. She raises the jar triumphantly in the air as a large sun rises below it, symbolising health, happiness, life, growth and renewal (see O’Hagan, 2023 for more on the use of sunshine in advertisements). “I am no luxury,” the Oatine cream continues, “Rather, I am a necessity for every woman who wishes to keep her skin clear and soft.” This personification creates empathy with consumers and has been proven to make brands more accessible and understood (cf. Delbaere et al., 2013).

Despite its initial success, by the early 1930s, sales of Oatine decreased amid growing competition from other face creams by both national and international brands. In an attempt to reach a new audience, Oatine began to target men in its advertisements (focusing on razor burn). However, by the end of the decade – exacerbated by supply issues during World War Two – the product had disappeared from the Swedish market. Oatine continued to be sold in Britain into the 1960s, but advertisements stop after 1962, indicating the company’s demise.

Today, as consumers increasingly desire natural skincare products, oat-based cosmetics can be found on the market once again. However, protecting body health and wellbeing is now extended to protecting environmental health and wellbeing. Using oat-based products is, therefore, no longer just about women fulfilling their ‘female’ duty to look good, but also fulfilling their ‘moral’ duty to be sustainable consumers.

A huge thanks to Dr Lauren Alex O’Hagan

The Open University & Örebro University